Un antoninianus présentant un revers nouveau, frappé à Antioche au cours du règne de Gallien comme seul auguste, est apparu récemment sur le marché. Il illustre une cérémonie de profectio et permet de compléter nos connaissances des déplacements impériaux et de la politique impériale dans les provinces orientales pendant les années 263-265, une période généralement considérée comme «sédentaire».

*This article has been a long time in the coming. I would like to thank Mr. Jean-Marc Doyen for his invitation to submit to the CEN as well as both Mr. Roger Bland, of the British Museum, and Mr. Richard Kelleher, of the Fitzwilliam Museum, for their assistance in tracking down a particularly difficult reference. Also of great aid were Ms. Caroline Baril, Mr. Marc Breitsprecher, Mr. Eric Mensch, Mr. Christian Lauwers and Mr. Jos Hemmes.

PM TRP XII C VI PP – profectio, and its numismatic context

In early 264, Gallienus planned a trip east ; such a trip would have surely included a stop in the important mint city of Antioch. For reasons which we will never know for sure, the trip never occurred or, perhaps more accurately, never occurred in full. The goal of this article will be twofold : (1) to introduce and discuss a previously unrecorded coin type minted at Antioch in 264, and (2) to postulate on the numismatic context and purposes of such a variety.

The coin in question is an antoninianus, minted in the name of Gallienus at Antioch. It is dated to 264 (fig. 1)1.

The style of the coin is that of the mint at Antioch in the mid-260s ; the dated reverse – PM TRP XII C VI PP, during the 12th tribunician power and 6th consulship of Gallienus – is early 264. The obverse legend, GALLIENVS AVG, is typical for the mint and the period, bearing only the name of Gallienus and his official title of Augustus. More interesting is the reverse type of the coin, showing the emperor on horseback trotting right and carrying a transverse spear. This iconographical imagery is typically reserved for the Roman ceremony of profectio2.

The type presented here has a direct corollary to another type presented by D. Dziewulski 3. The coin presented in that article is a rare and celebrated type also from the mint at Antioch, bearing an identical reverse legend, but displaying the typical adventvs scene (henceforth ‘ADVENTVS type’) : emperor on horseback, trotting left, right hand raised in salute, the left holding a sceptre (fig. 2)4. D. Dziewulski speculated that the coin could provide the basis for an argument that Gallienus had either travelled to the East, in or around 264, or at the very least had made plans for the voyage5.

That the two types presented here are directly related is beyond doubt. What remains is the question of their respective place(s) in the corpus of Gallienus’ Antiochene emissions. Taken together they may be able to shed more light on imperial policy towards the East in the mid-260s.

The coin presented here bearing the typical profectio reverse (henceforth : ‘PROFECTIO’) is of the characteristic ‘eastern’ style of the engravers of Antioch and is conveniently dated – TR(ibunicia) P(otestas) XII and C(os) VI – to the first part of 2646. The ADVENTVS type (above) has been known since at least the seventeenth century and was heretofore seen as a stand-alone type in Göbl’s 12th Antiochene emission 7. The two types – ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO, unmarked in the exergue – fit the requirements for the 12th emission. More importantly, they are also directly related to another Antiochene reverse which also bear the dated legend TRP XII C VI PP : a radiate lion walking left, lenching a thunderbolt in its mouth (fig. 3).

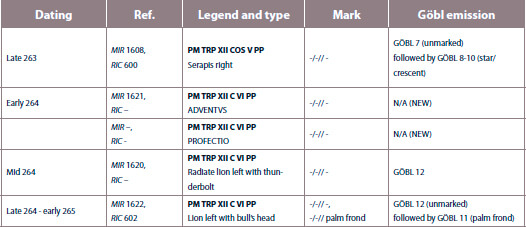

Göbl’s 12th emission is part of the second series of coins minted at Antioch following its reopening in mid-263 8. The most complete source for the coinage of Gallienus is Robert Göbl’s posthumous Die Münzprägung des Kaiser Valerianus I., Gallienus/ Saloninus (253/268), Regalianus (260) und Macrianus/Quietus (260/262) (MIR 36, 43, 44) – all future coin references will be to this work primarily. It is now recognized that the editors of Göbl’s text reversed the order of the 11th and 12th Antiochene emissions. While the two emissions are clearly interconnected, the discovery of the PROFECTIO type helps to confirm that the two emissions are distinct and in need of a certain revision. Based on the dating, the use of the B1l bust type and the use of the palm frond as an exergual mark, Göbl’s 12th emission (unmarked) must precede the 11th (palm frond) in the series.

Emissions 11 and 12 are very closely related and offer a variety of new reverse types over previous emissions. At Antioch, the radiate lion reverse, with hunderbolt, exists only for Gallienus’ 12th tribunician power (TRP XII), with three distinct bust types : bust left (A1), draped and cuirassed right (D2) and cuirassed left (B1l). This 12th emission is the only from the mint at Antioch to use this B1l bust and as such, becomes one of its defining features.

Göbl’s 11th emission begins with another lion reverse ; lion (not radiate), left with a bull’s head between its paws (MIR 1622). This reverse is also dated, but to Gallienus’ 13th tribunician power (TRP XIII). Interestingly, this type straddles both the 12th and the 11th emissions as it exists both with and without the palm frond as exergual marker. This mark in the exergue is, in fact, the primary indicator of the 11th emission (see fig. 4).

Our ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types are directly connected to the earlier type with the radiate lion and identical reverse legend (fig. 3). The ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types, however, depict important imperial ceremonies and would have, as such, immediately preceded the general run of the 11th emission types. The date then, for both types, is the beginning of 2649. Table 1 below provides an outline of where this pre-emission would be placed. It is likely that these types were intended as a precursor to the new series (emissions 11 and 12) 10 . In any event, the minting of these types was short lived.

Why this type, why 264 ?

The eastern part of the empire following the invasion of Shapur and ulminating with the advent of Odenathus was often a confused and turbulent place 11. Changes were afoot both politically and militarily. Following the capture of Valerian, the expulsion of Shapur and the ultimate usurpation and defeat of the Macriani there was a distinct vacuum in the power structures of the region. This vacuum was filled, in short order, by the Palmyrene prince Odenathus who, following the events of 261, was the de-facto ruler of the eastern Roman provinces in both name and right 12.

His relationship with Rome, and the consequences this entailed, would define the history and fortunes of the Roman near-East for the next decade. Following the suppression of the Macriani, Gallienus seems to have been content leaving Odenathus in relative control of the eastern provinces while he concentrated on the many problems that had beset the central and western parts of the empire. While not optimal, Gallienus’ stance of leaving the East in the hands of a willing and cooperative client-king cum Roman dux, was in keeping with his general military policy of assigning provincial problems to his generals. In the context of his then-ongoing western concerns, Gallienus was more than willing to delegate power to a capable commander who had no apparent imperial (Roman) aspirations of his own 13.

Following its reopening as a mint in 263, Antioch seemed to flourish under Palmyrene supervision. Numismatically, the city served as the main mint for the eastern provinces during Gallienus sole reign, though minting also occurred at auxiliary/military mints at both the beginning and end of the reign 14. We must look for an answer regarding the purposes of the ADVENTVS

and PROFECTIO types within this setting. Typically these types, when used together at an imperial mint, would indicate the coming and eventual going of an emperor to a region or a city – often Rome but, not always 15. There seems to be several possibilities as to why these types would be produced at this particular mint and at this particular time.

Production by the central empire ?

There is merit to the idea that these types could have been used by the authorities of the central empire, perhaps as a less invasive effort to reassert a ‘Roman’ influence upon the East. By 264 there had not been a unifying Roman presence (i.e. Emperor or mandated imperial representative) in the eastern provinces since the arrival of Valerian in 258. Despite the chaotic nature of the East in the first half of the 260s, the central empire was attentive to the many regional developments under Odenathus’ stewardship. Communications between Rome and Palmyra were both stable and constant. In fact, multiple sources report that it was Gallienus who invited Odenathus, upon hearing of the latter’s success over Shapur, to complete the destruction of the traitorous family of Macrianus by attacking Quietus who was then holed-up in Emesa (modern Homs, Syria). This cooperation and communication is further indicated by Gallienus adopting the titles of Persicus and Parthicus Maximus, while simultaneously bestowing further military powers and titles on Odenathus. There is even an idea that Gallienus celebrated a triumph in Rome for Odenathus’ eastern victories 16. With the above in mind, it seems unlikely that Gallienus would have chosen this time to act against Odenathus in any meaningful way much less through the passive medium of coinage. The ‘offended sensibilities’ (SOUTHERN 2001, p. 101) of the Roman upper classes, upon hearing the news that a non-Roman or barbarian was in direct control of several Roman provinces, was not a significant enough factor to motivate an otherwise embattled Emperor.

Production by Palmyra?

A somewhat reverse argument, that Odenathus had these types minted to commemorate his own victories against Shapur and Quietus, without approval from Rome, also requires discussion. With the reopening of the mint at Antioch in 263 all products displayed the bust and the name of the emperor in Rome. There is, however, evidence that it was Odenathus who controlled the mint’s activities. In 1989, J.-M. Doyen argued that Odenathus had the ADVENTVS (along with the Antiochene aurei and small bronze medallions, Ae asses), minted in order to distribute them himself as a donativum. As compelling as the idea appears, there is no evidence either literal or numismatic, that such ever occurred. The aurei (MIR 1614) and the asses (MIR 1610 d) clearly belong to the series beginning withthe dated reverse TRP XII C V (Serapis r.) and the longer obverse legend of GALLIENVS PF AVG – 263. These would not have been in production at the same time as those dating to TRP XII C V – 264 17. In any instance, an act of this nature – the minting of coinage for ones own purposes – by a client-king would have been seen in Rome as that of a usurper.

If Odenathus was indeed responsible for the minting activities of Antioch he could have also used the ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types to increase his renown locally, while maintaining the delicate relationship he had recently fostered with Rome 18. The use of coinage as propaganda was not new and it is clear that the Antiochene antoniniani from 264-265 take on a very different character from the coins of the initial series from Antioch. The 11th and 12th emissions depict an overwhelming aura of peace through Roman military dominance 19. This argument, along with the fact that Odenathus never committed any overt act against Rome between 261 and his assassination in 267, at the height of his power and (relative) independence, is indeed telling of his political aspirations. In actuality, there is good evidence that Odenathus’ dynastic intentions lay not west in Rome but farther east in Ctesiphon20.

Given Odenathus’ behaviour following the retreat of Shapur it seems unlikely that he would have gone through such lengths to undermine the nominal authority of Gallienus, especially when he was already corrector totius Orientis and possibly also the self-styled dux Romanorum in control of every Roman possession from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates 21. When all is considered, there was no readily apparent reason for Odenathus to consider breaking with Rome.

Eastern bound ?

The most obvious explanation for the ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types was that they were intended to announce and/or commemorate an imperial visit to the East, and more particularly to the mint city of Antioch. Admittedly we lack direct source material attesting to such a trip. The written sources are quite clear that Gallienus never travelled farther east than Athens, and maybe Byzantium. This period was often seen, by ancient and past historians, as Gallienus’ ‘sedentary’ or ‘Roman’ period of relative inactivity. The exact date and motives for the visit to Byzantium remain somewhat obscure 22.

It is noteworthy that imperial visits to the East in the mid-third century were a rare occurrence. Most emperors had neither the time, inclination nor necessarily the resources required for such an undertaking. Other than Valerian in the years immediately preceding his capture, only Gordian III was known to have set foot on eastern shores, and that only in 244 immediately prior to his suspicious death. Of interest is the coin pictured in fig. 5, an antoninianus of Gordian III, minted at Antioch in 238. It depicts a reverse almost identical to the ADVENTVS issue of Gallienus and is, in fact, the only other example of an adventvs ceremony from the mint at Antioch in this period. This type has been used by various scholars to hypothesize that the young Gordian III made an initial tour of the eastern provinces, upon his elevation in 238 23. However, no written sources record this trip.

Here we are provided with a precedent for the use of an ADVENTVS type for a probable adventvs ceremony at Antioch. By this logic, we can assume that both the ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types, in the name of Gallienus, were meant to commemorate their respective adventvs and profectio ceremonies in 264.

The initial purposes for such a trip would have been twofold : (1) to restore and improve imperial influence over the region, especially in light of Odenathus’ thenstill recent successes, and (2) to inspect and replenish the local legions and to tour and plan for fortifications for central and outlying eastern cities. All of this would have been within the context of the constant Gothic and Persian military threats 24. Given the relative stability of the situation in the central provinces by 264, a trip of this nature would not have been entirely out of the question as it would have been only a few years earlier. It is likely that Gallienus’ presence in Greece and the Balkans, in the fall of 264, was directly related to this planned trip to the East. Without a doubt, the undertaking of such a trip required extensive planning. Word of the emperor’s visit would have preceded his arrival by many months and certainly would have been important news in Antioch and the outlying principalities 25. The imperial mint at Antioch would have received directives to begin preparations for a special series of coins announcing both the emperor’s arrival as well as his eventual departure. This was the purpose of the Antiochene ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types. The relative rarity of these two types speak to the fact that their production was either very limited or, more likely, ceased when word reached Antioch that the trip had been called-off 26.

The fact that both types are dated to the first part of 264 comes as no surprise. Valerian’s capture meant that Gallienus had inherited what would soon become a turbulent Empire. Meanwhile, the revolt of the Macriani and the departure of the imperial army for Europe allowed Odenathus a virtual free military reign from 261-264 in the eastern provinces.

In the face of a perhaps overly successful client-king and a near fractious empire, Gallienus would have wanted to announce his presence to the peoples of the East as soon as he was viably able to do so 27. In all likelihood, the antoniniani depicting the respective ceremonies of adventvs and profectio were part of a larger plan, a joint effort on the parts of Rome and Palmyra (if not Gallienus and Odenathus themselves) to calm the eastern front and to project strength through the empire. These coins would have been meant to coincide with a visit to the East by Gallienus.

The early years of Gallienus’ sole reign were undeniably difficult. The capture of Valerian and the loss of direct control over the East in 260 coincided with other, more pertinent and immediate, problems for Gallienus. The revolt of Ingenuus, followed by an invasion of Alemanni and other tribes was but the first of the many problems to manifest. By the Fall of 260 Saloninus was dead and Postumus had officially broken from Rome. The following months leading into 261 saw the near simultaneous revolts of Regalianus, in Pannonia Superior, and the Macriani who proceeded to march towards Europe. Lucius Mussius Aemilianus, the praefectus Aegypti and a sympathizer of the eastern usurpers, was likely spurned into a revolt of his own, in 262, following the defeat of these latter. With the judicial use of his skilled generals, Gallienus tamed those threats which directly impacted Italy and Rome, but at a severe cost : Gaul and the western provinces were lost, at least temporarily, to Postumus while the East, not lost per se, was no longer under any direct or realistic imperial control.

Gallienus celebrated his decennalia in the latter part of 262 ; the first emperor to do so in over a quarter of a century, and the next two years proved to be the calmest of his sole reign. Unfortunately, this period between 263-265, Gallienus’ so-called « sedentary Roman period », is not well covered by the primary sources 28. Following the decennalia and an abortive invasion of Gaul, which ended in a stalemate, Gallienus began to look eastward. A trip to the East, including Antioch, was required for the stability of the Empire and was certainly plausible. The travel began in Illyricum, followed by northern Greece and would have included Byzantium, or Miletus, before western Anatolia and onto Antioch. This was likely the plan, but as history shows, Gallienus never got any further than Greece before he was called back to the western front.

R. Bland, in his 2011 article, states, “Both events – the striking of gold coins and the use of the Adventus type – have been used as evidence for the presence of the Emperor at the place of minting. In the case of the unique aureus, this is probably not to be relied on… As for the Adventus type, that would seem to provide better evidence for a visit by Gallienus to Antioch, but this is not certain” 29.

This statement can now be strengthened by the inclusion of the PROFECTIO type. If its sister-type ADVENTVS was ‘better evidence’ for an expedition east by Gallienus, then certainly the addition of the PROFECTIO type would seem to confirm that an imperial visit to Antioch was planned for mid-264. The limited number of known specimens for each confirms that said trip was abandoned, but only after the mint had been ordered to produce the respective ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types in anticipation of the emperor’s presence.

Fig. 1 – GALLIENVSAVG

Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right viewed from rear (D2).

PMTRPXIIICVI[PP] -/-//-

Emperor on horseback trotting right, holding transverse spear in right hand.

Billon : 3,84 g ; 12h ; 22 x 23 mm.

Cohen – ; RIC – ; MIR –.

Fig. 2 – GALLIENVSAVG

Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right viewed from rear (D2).

PMTRPXIICVIPP

Emperor on horseback trotting left, right hand raised in salute, left holding a sceptre, -/-//-

Billon : 3,41 g ; 12h ; 23 x 21 mm.

C. 840 ; RIC – ; MIR 1621 i.

1. All images are property of the author unless otherwise indicated.

2. See MANDERS 2012, p. 701, SUMI 2005, p. 35 and MACCORMACK 1981, p. 40-43, for a more complete discussion of the respective ceremonies of adventvs and profectio.

3. DZIEWULSKI 1986-1989.

4. See C. 840 and MIR 1621 i. The authors of RIC either did not know the type or ignored its existence. See DZIEWULSKI 1986-1989 for an initial detailed discussion of the type. DOYEN 1989, p. 199, knew of three specimens including that referenced but, not pictured, in COHEN 1880-1892 ; BLAND 2011, p. 137, note 9, knew of four. This author currently knows of 7 examples : 1 – Münz Zentrum, Cologne, Auction 58 (1986), #2110 ; 2 – H. J. Knopek, Cologne, #7, 1978, #796 ; 3 – DZIEWULSKI 1986-1989 ; 4 – the BM example ; 5 – MIR 1621 I – from a ‘Private Collection’ ; 6 – currently in a French private collection, and 7 – that shown here from the collection of the author. These 7 coins come from 4 different reverse dies, indicating that the potential number of specimens could be significantly higher.

5. The «East» is an unavoidably vague term that includes, for the context of this article, the provinces of Mesopotamia, Palestina, Arabia, Cilicia, Cappadocia and parts of south-eastern Asia Minor. See BLAND 2011, p. 136, note 6, for an overview of the extent of Odenathus’ control.

Fig. 3 – GALLIENVSAVG

Busts A1, D2 and B1l

PMTRPXIICVIPP, -/-//-

Radiate lion left with thunderbolt

MIR 1620 f (C. – ; RIC –), 1620 i (C. 842 ; RIC –), 1620

l (C. – ; RIC –)

Fig. 4 – GALLIENVSAVG

Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right viewed from rear (D2).

PMTRPXIICVIPP-/-// palm frond

Lion left with bull’s head

MIR 1622 i (C. 844 ; RIC 602 A), 1622 c (C. 844 ; RIC

602 A – with frond) (not all bust varieties shown)

6. Precise dating of the Antiochene issues TRP XII and TRP XIII remains difficult. See GALLWEY 1962, p. 358-360, ELKS 1975, p. 100-103, BASTIEN 1967, p. 237, DE ROQUEFEUIL 1970, p. 120, REDÖ 1985, p. 105, 114, GÖBL 2000, p. 130-131 and ARMSTRONG 1987a in general. For the so-called eastern style, see RIC V-1, p. 24 : “but during the sole reign of Gallienus the eastern coins struck in his name and that of his empress are of a totally different character, being smaller and thinner, with small busts in low relief, occupying less of the field”, and, “in other series the products of the mint at Antioch are easily identified, being mostly wellstruck and neat, and of eastern workmanship”.

7. The type was known to Cohen (C. 840) who quoted VAILLANT 1674, as his source. For the type and order of emissions see GÖBL 2000, p. 130-1, table 48, plates 115-6.

8. For the sake of ease this author will retain the general outline of emissions put forth by Göbl, albeit with a minor modification. See also BLAND 2011, p. 136, and DE BLOIS 1975, p. 112.

9. By 264, Antioch had stabilized (following the earlier Persian assaults) to the point where the mint was operating on typical imperial processes with 8 officinae. See REDÖ 1985, p. 104-105, GALLWEY 1962, p. 359 and ELKS 1975, p. 100-102 for a general discussion of the officinae and the use of the palm frond as an exergual marker.

10. REDÖ 1985, p. 105, hypothesizes that the TRP XII types should fall into a short-lived pre-issue run prior to Göbl’s 11th and 12th ; he further defines TRP XII as one of the ‘additional elements’ of an unmarked pre-issue to Göbl 11 (p. 114). However, he too was ignorant of the ADVENTVS and PROFECTIO types. See also SOUTHERN 2001, p. 97 : “mints produced good quality gold coins and medallions”, wherever Gallienus was present. This would apply to ceremonial antoniniani as well, and bolsters the argument for a pre-issue to Göbl’s 11th emission. DE BLOIS 1975, p. 89, is similar in the statement that after 260 all gold coinage (and, by extension, ceremonial antoniniani) was issued apart from normal regular coinage. DOYEN 1989, p. 196-197, argues that the aurei (MIR 1614) and small medallions / Ae asses (MIR 1610 d) minted as part of the initial series from Antioch would have been associated with these ceremonial antoniniani.

11. The general history of the period is well known and will not be repeated here. For a general overview see both DE BLOIS 1976 and BRAY 1997.

12. On Lucius Septimius Odenathus see PLRE I (p. 638) ; for the man himself see SOUTHERN 2008 (p. 61-70), DOYEN 1989, p. 195, DE BLOIS 1976, p. 1-3, 34 and BRAY 1997, p. 114-119, 144-48 for a complete list of Roman and Palmyrene military titles.

13. POTTER 2004, p. 260. This laissez-faire attitude would set, in historical retrospect, a dangerous precedent which would ultimately be expressed in Aurelian’s retaking of the East by force in 271-272. From 259-267, Gallienus often delegated military matters, especially outside of the central empire, to a number of military men : most notably he relied on Postumus to look after Gaul when he travelled to the Balkans in 258-60 ; on Aureolus, in 260, to help suppress the revolt of Ingenuus and then to either press or contain Postumus from 261-267, and on Odentathus as his regent of the East, from 261 until the latter’s assassination in 267. Gallienus also relied on sub-generals – or men less well-known to posterity : on both Ingenuus and Regalian for defense of the Pannonian provinces ; Domitianus (under Aureolus) versus the Macriani in 261 ; Aurelius Theodotus in Egypt in 262, against Aemilianus and Memor ; and later, in 267, on Marcianus to counter the Goths in Achea and Illyricum. Also in 267 he sent the Praetorian Prefect Heraclianus (the man rumoured to have later delivered the killing blow) to the East, following Odenathus’ death, in an attempt to either regain influence against Zenobia or to regain the East by force. It is notable that the majority of these men, in their own time, attempted to seize the purple.

14. For the minting at Emesa see GÖBL 2000, p. 132-5, tables 50-1, plates 119-23, for the minting at Cyzicus (the ‘SPQR Mint’, now better understood to have been located at Smyrna) see GÖBL 2000, p. 122-7, table 45, plates 45-6.

15. BLAND 2011, p. 137. It should be noted that the adventvs and profectio ceremonies seem to have been used interchangeably in the third century and could be taken to mean entry into a foreign city and departure therefrom as well as departure from Rome and re-return thereto (DZIEWULSKI, 1986-1989, p. 30, quoting STEVENSON 1964). The greater known number of ADVENTVS coin examples strongly implies that this type was produced well in advance of PROFECTIO. ADVENTVS was used as a reverse type at

several mints by Gallienus during his sole reign. See MIR 337, 377, 435 and 656 for Rome ; MIR 1026 for Milan ; and MIR 1422 (with emperor on horseback trotting right with hand in salute) for Siscia. Similar known types include BONVS ADVENTVS AVG at Siscia (MIR 1432). Also see GENEVIÈVE & HOLLARD 2004, and PM TRP XII C VI PP (MIR 1620) at Antioch. PROFECTIO, was not a common reverse type and appears to have only been used once, other than our PM TRP XII C VI PP, see MIR 1047 (mint of Milan – 261) for an eight-weight multiple of an aureus, depicting Gallienus on horseback trotting right, crowned by Victory and holding a transverse spear, and being led (out) by a soldier. MIR 896, an ‘Abschlage,’ is an uncertain coin and is here discounted for the purposes of this study.

16. On the communication between Palmyra and Rome see SOUTHERN 2001, p. 97-102 and SOUTHERN 2008, p. 70. Odenathus besieged Emesa in late 261, see ZOSIMUS (1.39), EUTROPIUS (9.10), SYNKELLOS (466), BRAY 1997, p. 144 and DOYEN 1989, p. 195. See also SOUTHERN 2008, p. 63-70, note 17. Though doubt remains on whether or not Odenathus was styled dux Romanorum he was certainly granted auxiliary Roman military forces. See DODGEON & LIEU 1991, Appendix 4 (p. 336), for the use of the titles Persicus and Parthicus Maximus, apparently adopted in 263 and known only in inscriptions. See HA (10.5, 12.1) for Gallienus ordering the minting of coins in Odenathus’

honour : “vocavit eiusque moneta, que Persas captos traheret, cudi iussit”. Such pieces are not known. Odenathus was not made co-augustus by Gallienus as is claimed by the author of the HA (12.1). See also MIR 566 : a four-weight multiple of an aureus, from the mint at Rome in 264, with Gallienus riding in a processional chariot with the matching reverse legend PM TRP XII COS VI PP.

Fig. 5 – IMPCAESMANTGORDIANVSAVG

Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right viewed from rear (D2).

PMTRPIICOSPP, -/-//-

Emperor on horseback left, right hand raised in salute, left holding a transverse spear.

RIC 174 (Image courtesy of Pecunem, Auction 9, Lot 660)

17. Despite his argument for the donativum, DOYEN 1989, p. 195-199, recognized the difficulty in reconciling this joint production of gold and bronze types with that of the ADVENTVS : “Nous pensons toutefois qu’il est plus logique de considérer la série d’or comme contemporaine des premiers antoniniens frappés en Syrie sous l’autorité d’Odenath” (p. 199).

18. PLRE I, p. 638. See POTTER 2004, p. 259 and SOUTHERN 2001, p. 97. Odenathus seems to have gone out of his way to make himself known to Antioch, reportedly choosing a site just outside of the city, and not near or in Palmyra, to assume the typically Persian title of ‘King of Kings.’

19. HA 12.1 echoed by DE BLOIS 1976, p. 135. Göbl’s 12th emission is very militaristic in nature, introducing several new reverse types depicting peace gained through military means or in praise of the military : the very rare FVNDATOR PACIS (MIR 1624), IOVI PATRI (MIR 1625), MARS VICTOR (MIR 1632) and PAX FVNDATA (MIR 1635). It is

noteworthy that several of these reverse types were used for the first time at Antioch and remained in use exclusively at eastern mints during Gallienus’ reign unlike the more common, yet still martial MINERVA AVG (MIR 1634) and VIRTVS AVG (MIR 1636).

20. POTTER 2004, p. 260 and PARKER 2009, p. 343. Odenathus’ uses of his hereditary and assumed titles (e.g. King of Kings) implies that he was more interested in challenging Shapur for the control of Persia than Rome. But this need not always have been the case. Evidence suggests that prior to 259-60 Odenathus was biding his time pending the outcome of the ongoing Roman-Persian hostilities, see DE BLOIS 1975, p. 12-14. PETRUS PATRICIUS (frag. 10), implies that Odenathus courted Shapur immediately before the latter’s invasion of Syria.

21. During this period Odenathus was the near-complete, if not complete, master of the eastern Roman Provinces. This control, however, seems to have been mostly military in nature, see ZONARAS (12.23), BLAND 2011, p. 172. See BRAY 1997, p. 139, arguing that the title of corrector totius Orientis was civil in nature and granted no imperial authority. This title had precedent in Priscus, whom Philip II styled rector Orientis in 244 (see SOUTHERN 2008, p. 71). SYNKELLOS (466) confers the title dux. See SOUTHERN 2008, p. 65, for the argument that Odenathus might have chosen for himself the title of dux Romanorum/Oriens, when nothing further was forthcoming from Rome, because it would simultaneously confer and justify his further military powers over local Roman forces, while not necessarily antagonizing the central empire. There is no concrete

evidence that Odenathus was ever conferred, or used, the title imperator (SOUTHERN 2008, p. 62-3).

22. See further BRAY 1997, p. 215, FITZ 1976, p. 5-6, and ARMSTRONG 1987a, p. 237. ALFÖLDI 1977, p. 43, mentions, “the expedition of Gallienus to Asia Minor”, though this is not explained further. It may be that Alföldi is referencing Gallienus’ supposed tour of the battlements at Byzantium in 264, see HA (7.2). ARMSTRONG 1987b, p. 241, followed by SOUTHERN 2001, p. 104, dates the trip to Byzantium, to quell a revolt, to 262. DE BLOIS 1976, p. 3, dates the visit to Byzantium to 263. DZIEWULSKI 1986-1989, p. 31, quoting from ALFÖLDI 1939, hypothesizes that Gallienus was in Miletus in 263, again on an inspection tour. Both BRAY 1997, p. 274, “no reason to believe that Gallienus, during the course of his reign, ever went further east than the Aegean coast of Asia Minor”, and DOYEN 1989, p. 197, “il est bien certain que Gallien, retenu

sur le front occidental, n’a pas pu se rendre à Antioche, même très brièvement”, are against the possibility of any such trip.

23. See MICHAUX 2012, p. 87 and BLAND 2012, p. 526, for discussions of a probable, initial visit by Gordian to the east in 238-39, years prior to that in 243-244. It is noteworthy that Philipp ‘the Arab’ was not yet emperor when he travelled east with Gordian in 244, and never returned afterwards.

24. See SYNKELLOS (467), and HA (7.3-4), PFLAUM & BASTIEN 1969, p. 11, ARMSTRONG 1987b, p. 241, DE BLOIS 1976, p. 124, and most importantly DE BLOIS 1975 for discussions of the persistent Gothic incursions into Asia Minor in 263-265. EUTROPIUS (9.10) shows that Odenathus appears to have been active against these latter prior to his invasion of Persia. On the inspection tour, see ZOSIMUS (1.39), EUTROPIUS (9.10) and BRAY 1997, p. 215 : “it is probable that like so many of his predecessors he (Gallienus) made himself personally acquainted with provincial conditions and not only in border areas”.

25. The author is grateful to J.-M. Doyen for the insight that there is also a lack of local provincial coinages (Asia Minor) attesting to any imperial travel in 264. This, and the fact that Gallienus was in northern Greece and the Balkans in late 264 implies that the trip east had been called off earlier in the year.

26. See ALFÖLDI 1977, p. 29, note 23, for discussion of the pre-preparation of dies in relation to significant events (in relation to the dated issues at the mint at Cyzicus (Smyrna)). This is echoed by DOYEN 1989, p. 197-198 : “Ou bien ces monnaies ont été préparées en vue d’une visite impériale annulée pour des raisons inconnues”. The ADVENTVS type is now known by 7 examples from 4 reverse dies while the PROFECTIO, so far, is unique. This variance implies that the ADVENTVS was put into production before the PROFECTIO, which, in turn, was probably only produced for a very short while before word reached Antioch that the planned trip had been cancelled. The result of which was that those which had been produced were most likely never intended for actual circulation.

27. Gallienus could not have had any realistic intentions of ousting Odenathus at this point ; he had neither the resources, stability of empire nor the geographic capability. Any such trip would have been purely political and in the finest tradition of imperial grandstanding, see SOUTHERN 2001, p. 101-102. Hadrian would have been proud.

28. DZIEWULSKI 1986-1989, p. 31. Both Zosimus and Zonaras, our main credible sources, omit any mention of imperial activities during this period. The notoriously untrustworthy Historia Augusta similarly omits any direct mention of activities during this period. Most source material, including these three, take the opportunity to attack Gallienus’ poor rule, indolence, personal habits and lack of political acumen ; see as well AURELIUS VICTOR (33) and EUTROPIUS (9). Gallienus was no longer so preoccupied with Postumus starting in early 263, with the installation of Aureolus and the then-new cavalry units at Milan (FITZ 1966, p. 71), but was again active as early as the spring of 265. Postumus had also ordered the removal, and probable murder of Gallienus’ middle son, Saloninus Valerianus. SOUTHERN 2001, p. 81-102 and POTTER 2004, p. 215-298 (specifically p. 257-263) and DE BLOIS 1976 (p. 3-8) give the most concise summary of events on the western front 262-65. See DRINKWATER 1987, p. 92-108, for a summary of the hostilities between Gallienus and Postumus.

29. BLAND 2011, p. 137. DE BLOIS 1975, p. 209, shares a similar opinion.